By Andy Douglas

The major theme of Vincent Bevins’ book “If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution” can be discerned from its subtitle. Plenty of protests, demonstrations and political uprisings rocked the globe in the decade Bevins refers to – the 2010s. Actual, lasting and beneficial change, not so much.

His argument, drawn from years of reporting on social movements and uprisings, is that most of these protests suffered from a lack of vision for what would come next. Bevins reminds us of the mass uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Syria, Libya, and Bahrain, later termed the Arab Spring. Also the Maidan in Ukraine, uprisings in Brazil, Hong Kong and Chile, and others around the world. However, seven of these countries experienced something worse than failure –they went backward. Only in Chile did something approaching substantial change occur, with voters calling for and achieving a new constitution.

There were similarities across many of these protests, which seemed to draw on a repertoire of spontaneous, digitally-coordinated, horizontally-organized, leaderless mass movements, which then created political vacuums. In Egypt, the military rushed into this vacuum. In Bahrain, it was Saudi Arabia. In Kyiv, a different set of oligarchs took power. In Hong Kong, Beijing rolled in. In Brazil, the Brazilian center-right blew open another hole in the social fabric by supporting presidential impeachment, and the far right filled that space.

Many observers were surprised at the degree to which conservative elites across many of these societies were organized and delivered top-down cultural revolutions instead.

The book is helpful in making sense of what happened in some complicated places, such as Ukraine, giving a detailed history of the various factions, historical factors, and ways in which all of these factions were perceived by the West.

Bevins also notes that the Arab revolutions were not economically radical. They were often more concerned with human rights and legal reform. Prevailing voices, both secular and religious, took the free market, property relations and neoliberal rationality for granted.

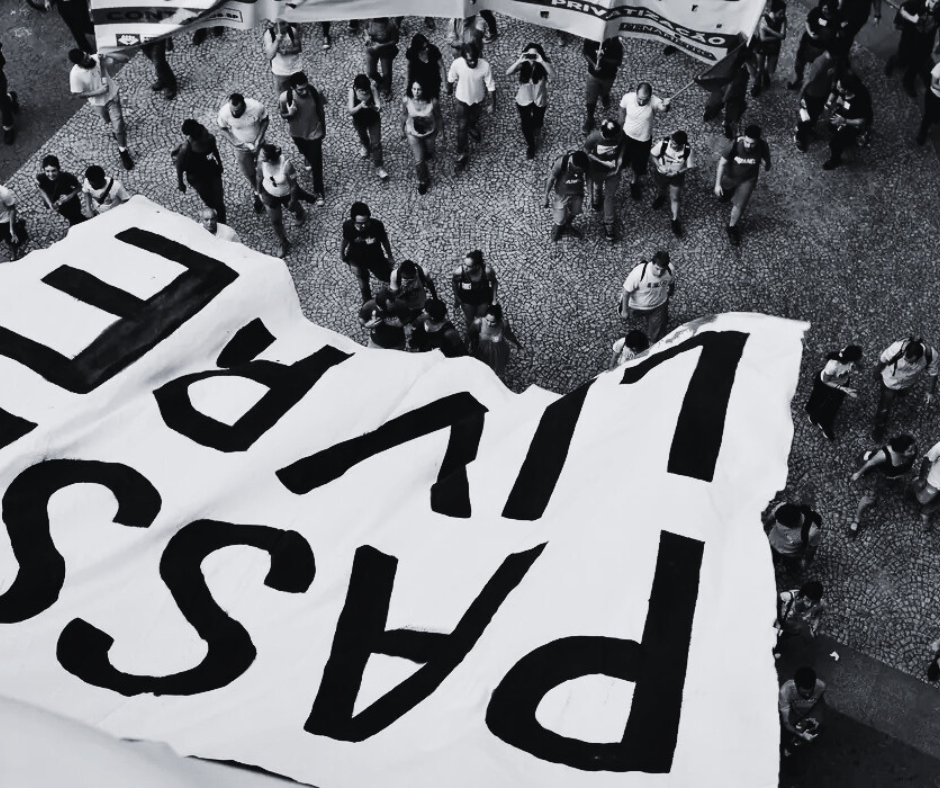

One of the more interesting movements Bevins highlights is the Movimento Passe Livre in Brazil. In response to a threatened price hike of bus fares, a group of young radicals met, discussed strategy, and took action, blockading the streets of Sao Paulo. They successfully shut down part of the city for days, but police responded with violence and the media tended to portray the protestors unsympathetically.

Like many of these movements, Movimento Passe Livre suffered from what Bevins calls “too much horizontalism”, a dynamic which reflects revolutionary debate for the past 100 years. Should the movement be leaderless – truly a mass uprising – or does it need structure, even hierarchy? As Pablo Gerbaudo, Italian sociologist, notes, at the end of the day, horizontalism is a reflection of individualism. I take this to mean that the reluctance to fit oneself into a larger movement because of individualistic sentiments, can doom a movement.

The other fatal flaw seemed to be that there was insufficient thought given to the day after. Movimento Passe Livre had made no preparations for what would happen after they successfully stopped the fare hike.

“If you burn down a building, divine providence doesn’t supply you with a better one,” Bevins writes. “You have to have a way to get from where you are to where you want to be, a roadmap, a plan, a strategy. Simply being right is not enough.”

A revolution doesn’t start and end in one moment. History continues to unfold after the explosion. The aspiration during this decade was too often: protests and crackdowns lead to favorable media coverage, which brings more people out to protest, which in some vague way leads to a better society.

The critical role of social media unites many of these protests. But the dominance of the US in the global media also casts a shadow. The media in the West has had a tendency to conflate struggles for democracy with a desire to join the club of rich countries. Like much of the internet, the major social media firms are all based in the US. Intellectual production happens in a way that reflects the hierarchical nature of the global economy.

There is also an important difference in approach between the global north and south. “In New York or Paris,” Bevins quotes one activist as saying, “if you do horizontal, leaderless, post-ideological uprising, and it doesn’t work out, you just get a media or academic career. Out here in the real world, if the revolution fails, you go to jail or end up dead.”

There are lessons here for those who would engage in the work of social transformation. Some takeaways from Bevins’ research:

- If demands can be made after a successful protest, someone must be ready to represent the group and negotiate.

- A group must be prepared to take the elites’ place and do a better job.

- The concept of retreat, to be able to wait and regroup, is important.

- Pay attention to who has the power to define the uprising.

- In the long run, these struggles can become part of something greater.

As Hossam Baghat, a Cairo activist, encourages, “Organize. Create an organized movement. And don’t be afraid of representation. We thought representation was elitism, but actually it is the essence of democracy.”

Let’s hope the next generation – those who have been protesting in Bangladesh, Nepal, the Philippines and other places – learn from what has gone before.