A NEW APPROACH

How to begin to move toward a different philosophy? And what policies might a Proutist approach to criminal justice embrace? Other countries have strikingly different approaches than the U.S. when it comes to the treatment of prisoners and success in rehabilitation. Germany and the Netherlands, for example, have significantly lower incarceration rates, according to the Vera Institute of Justice: “One of the biggest differences in German and Dutch prisons is the focus on ‘normalization’: making life in prison as similar as possible to life in the community. German and Dutch prison systems are organized around the ideas of resocialization and rehabilitation. The U.S. system is organized around incapacitation and retribution. Both countries rely heavily on fines or other community-based sentences, not prison sentences.”

There is also the example of Norway’s Halden-Fengsel Prison, which has been called the world’s most humane maximum-security prison. That facility is located in the south of Norway, just over the border from Sweden, inland from the North Sea. It’s surrounded by birch forest. You’ll find no razor wire, no electric fences, and no towers with snipers.

What you will find is plenty of access to sunlight and fresh air. The architectural design of the prison encourages stability. A large wall encircles the facility, but the prison emphasizes dynamic security, the idea that interpersonal relationships between staff and inmates are the primary factor in maintaining safety. Staff members receive thorough training, with an emphasis on establishing an atmosphere of “normalcy.”

Unlike the dining system in most American prisons, Halden allows inmates to cook nourishing food for themselves. They stay in individual rooms. Guards and inmates eat and play sports together. Assaults on guards are unheard of and solitary confinement is rarely used. When conflicts erupt between inmates, other inmates and chaplains sit down with them and mediate.

The Norwegian Correctional Service makes a reintegration guarantee to all released inmates, securing them a home, a job and access to a social network. Each released inmate is guaranteed a home and a job.

‘Better out than in’ is the Correctional Service’s unofficial motto. Guards are taught that treating inmates humanely is something they should do not for the inmates but for themselves. Officer Ragnar Kristoffersen says, “If you treat people badly, it’s a reflection on yourself.” Harsh treatment of inmates will, he believes, ripple outward into the officers’ lives, affecting their self-image, their families, even the country as a whole.

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE

Are there lessons to be learned here? Absolutely. But what will need to change in the U.S. and many other countries is the focus on retribution as opposed to restoration.

One promising trend is the development of “restorative justice” initiatives. These focus on the process of accountability for those who have committed crimes, helping them understand the impact their behavior has had on others, and responding to and repairing that harm. (A related approach, “transformative justice,” focuses on changing the social conditions that lead to crime and imprisonment.)

Attorney Bruce Kittle, who has served as a prison chaplain, describes restorative justice this way: “The community is not left on the sidelines to watch, but invited to be actively involved in their neighborhoods and communities in not only responding to crime, but expressing community values and creating resources and opportunities that eventually result in the reduction of crime.”

Buzz Alexander writes about a remarkable event he witnessed epitomizing this approach. In a Canadian indigenous community, elders gathered for a sentencing circle. They apologized to the wayward youth whose sentence they were determining. We did something wrong in raising you, they said, or you would not be standing here before us.

Such awareness of the way the offender is connected to the community is at the heart of restorative justice, the understanding that, when violence is perpetrated, the community itself frays. Achieving justice means offering understanding, healing, and restoration for all involved. This, of course, includes the victim. A crucial aspect of restorative justice lies in supporting crime victims and their needs.

“The engaged and inclusive process itself transforms people,” Bruce Kittle adds, “and when people are transformed, they in turn transform their communities and, eventually, the system. This is not ‘top down’ but a process that builds from the foundation of a community up.”

Such work involves the effort to promote healing among all parties. This includes recognizing that the one who caused harm is also a person.

The goal is to reach a consensus, led by the victim, on how to make restitution. The process helps both sides see each other as human beings. Maya Schenwar offers a caveat, though, for sexual assault situations: “Very often the victim does not want to be in a room with the perpetrator, even with counseling and after time has passed. We need to prioritize the victims’ needs in these situations. We can’t use the same model to deal with every offense.”

Mary Roche, restorative justice coordinator for the state of Iowa, says it’s vitally important that the piece about offenders’ individual atonement, and being accountable—the connection to the victim—is there. Offenders have to figure out how to make amends in an intentional way: to do something kind, with intention. Or to change their thoughts from “I have taken and taken,” to “Now I need to give something.”

NEUROPLASTICITY

There is a lot of up-and-coming research about how it’s never too late to reprogram the brain. How the brain’s ‘neuroplasticity’ allows for changes in behavior at any age. How what we practice, we become. This holds tremendous potential for people with addictions, and for those with criminal tendencies. “The very mechanisms in the brain that allow adversity to get under the skin are also the mechanisms that enable awakening,” says neuroscientist Richard Davidson.

I’ve talked about this with Sally Schwager. A Connecticut therapist, Schwager started volunteering a few years ago with the Osborne Association, an organization that offers a 12-week training in restorative justice counseling. She worked on something called the “Long-Termers Responsibility Project.” This program was designed to help inmates convicted of murder and saddled with a long-term sentence work toward atonement. The association vetted each individual with a particular end in mind: were they open to expressing remorse? And were they willing to take responsibility for their actions?

Any act of violence has a ripple effect, Schwager says. It affects the victim, the family, the offender him or herself, and the community in which the violence takes place. Putting together a team to work with each inmate, the Responsibility Project looks at the impact of this violence from many angles.

The program aims to help those who have committed crimes to feel what the other person feels. Remorse equals empathy.

Offenders also need to begin to feel compassion for themselves. They have to discover their own wholeness, in order to heal the brokenness that has contributed to the mindset that led to their crimes.

REHABILITATION

A retired prison superintendent (Minnesota Correctional Facility in Red Wing), Otis Zanders, says that while prison safety has to be a priority, “Good programming makes good security. If the offenders buy in to the program, they police themselves.”

“These are men in survival mode,” Zanders goes on. “We’re looking for ways to move them up Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to self-actualization.” (He’s referring to psychologist Abraham Maslow, who postulated a hierarchy of human needs, ranging from basic physical ones on up to trust, relationship, and self-understanding).

Being imprisoned is the punishment. There’s no need to intensify the experience. With that in mind, what do you do for prisoners once they’re inside? You focus on preparing them for reentry into society. You identify risk issues and treatment needs through assessment, and you use programming to change thinking. The emphasis is on changes in behavior.

Aspects of restorative practices evident in music and arts programs, for example, include problem-solving skills, conflict transformation, tools for improved relationships with family members, personal growth, self-esteem, respect, and strengthened communities. Teamwork, group order, social adjustment, new companionship, fair play and sense of cooperation, decreased prejudice and a healthy sense of community cohesiveness, all of these qualities have been noted in studies of music programs’ effect on insiders.

AVP

The Alternatives to Violence Program is an experiential program, helping people learn skills and attitudes that can lead to lives free of violence. The basic workshop introduces conflict resolution skills. Step by step exercises focus on Affirmation, Communication, Cooperation and Creative Conflict Resolution. Advanced workshops take a deeper plunge into the issues of Stereotyping, Power, Fear, Anger, Gender Issues and Forgiveness. It is one useful example of programs that help change behavior.

“Paying attention to detail was a new experience for me,” said one inmate who went through the program. Said another, “Trust and reliance on other people is hard to come by in prison. But here with each other and with the volunteer singers, we know that we can relax and enjoy each other. Most important, I’ve learned to trust myself.”

And, “In prison you have a tendency to hang around your own ethnic group. Coming to something like this you see those barriers disappear.”

Warden Jim McKinney believes rehabilitation begins when you get inmates to start to see past themselves. Shifting the focus off of themselves, they begin to develop empathy. And empathy is at the heart of rehabilitation.

But in many American prisons, writing and other remedial programs have been or are being cut back substantially. “I believe we began to incarcerate more people than the system could handle, and all treatment programs suffered with the buildup of what has been termed the prison industrial complex,” arts consultant Grady Hillman writes. “Suddenly prisons were all about bed space…as a financial resource and locating prisoners as a commodity market.”

“Many arts-in-corrections programs were running away from exposure,” Hillman continues, “fearful that the public would decry such programs as contributing to the common clichéd perception that we were somehow running country clubs.”

“Prison systems were hearing from the public and politicians that we needed to hurt inmates, not help them.”

EDUCATION

Many prisoners have been traumatized by the mainstream educational system. They’ve been pushed out of it, and told they’re failures. They may have lived an unstable life, in which education was not a consistent possibility. “Some have had 15 to 20 foster care placements, and that means 15 to 20 schools within four or five years,” Rachel Marie-Crane Williams says.

Research has shown that higher education programs in prisons can significantly reduce recidivism. “While this is an important benefit, college-in-prison programs provide many more benefits,” according to the Liberal Arts Beyond Bars program website. “Our project aims to provide opportunities that broaden horizons, develop students’ agency and increased civic engagement, encourage social change from the inside out, strengthen bonds with families and communities, break family legacies of incarceration, inspire inquiry and transformation, and create pathways for successful reentry with dignity and compassion

Unfortunately, many prisons offer little in the way of education and job training. However, although prison programs were slashed nationally in the ‘80s and ‘90s, educational efforts do continue at some prisons. Such programs are inexpensive to run; you don’t have to house or feed students, just pay the faculty.

SENTENCING

Sentencing reform must be a part of any shift to a more humane system. A New Yorker article entitled “How We Misunderstand Mass Incarceration” addresses the increasing role prosecutors are playing in the growth of incarceration. The author, legal scholar John Pfaff, believes there are three main causes of prison growth: unregulated prosecutorial power, structural political failures, and over-long punishment of people convicted of violent crimes. But prosecutors, acting with wide discretion and little oversight, remain the engines driving mass incarceration. Appointing rather than electing prosecutors might help, he suggests.

Recent decades have seen a trend toward tougher sentencing, on a global level. Prison terms are getting longer. Harsher sentencing is a driver of imprisonment, but has done nothing to tackle the underlying causes of crime. Prison population growth is currently fuelled by imprisoning fairly low-level, usually non-violent, offenders.

In almost every country, the law requires that offenders with previous convictions be sentenced more harshly than those without. But the evidence is that locking up repeat offenders has little impact on re-offending, according to Prisonstudies.org.

Over 2 million of the world’s prisoners are detained in relation to drug offenses (including possession for personal use). And around a third of all women prisoners are detained because of a drug conviction. “Excessive use of imprisonment for drug offenses has not deterred suppliers or prevented drug use, but has placed a huge burden on criminal justice systems. Punitive enforcement laws have exacerbated social and economic problems in communities affected by high levels of poverty, unemployment and drug dependency. Support is growing for treatment-based interventions.” (prisonstudies.org).

Around half a million of the world’s 11 million-plus prisoners are serving a life sentence. Some countries, like Brazil, do not use them. In the Netherlands, someone convicted of murder would be more likely to receive a custodial sentence of up to twelve years, followed by a period psychiatric treatment.

“Life sentences, particularly those imposed with excessive minimum terms or non-eligibility for parole, are widely seen as inhumane,” prisonstudies.org notes. “Their mental health impact is severe, due to the uncertainty or impossibility of release and the associated sense of hopelessness.”

American scholar William Stuntz believes the current justice system suffers from “procedural prejudice.” There’s too much red tape, too much tying of the judge’s hands. Stuntz believes we should go into court with an understanding of what a crime is and what justice is like, and then let common sense and compassion take over.

In other words, mercy and true justice—a blending of compassion and reason—are what are required in any correctional system, not simple, blind procedural fairness.

The fact that many defendants cannot afford bail, for example, perpetuates a cycle of poverty and jail time. It’s basically imprisoning people for being poor, even for things like traffic tickets and court fees.

JUSTICE

Achieving justice thus means offering a chance for accountability, healing, and restoration, for all involved, including the victim, in an engaged and inclusive process that builds from the foundation of a community up.

I appreciate the metaphor offered by Sarkar of society as a group of pilgrims traveling together in a caravan. If any of these travelers falls behind, or stumbles, or becomes ill, the group steps up and accommodates them, helping this person along the way. They don’t leave anyone behind. It’s about forward, collective movement.

Greg Boyle writes about working with gang members in Los Angeles. He started a business called Home Boy Industries to give jobs to ex-gangbangers. His book reveals the deep need in many of these gang members to feel loved and respected, and their desire to turn away from crime when offered these qualities in another setting. Reflecting on his approach, Boyle says, “We imagine a circle of compassion. Then we imagine no one standing outside that circle, moving ourselves closer to the margins so that the margins themselves will be erased. We stand there with those whose dignity has been denied.”

It might seem odd to describe a prison as a caring community. But if we hope to break the chain of criminal thinking, then that’s exactly the kind of environment we want prisons to be.

Engagement in pro-social activity, creative expression, the modeling of positive emotions, retraining of the brain as suggested by the idea of neuroplasticity, developing resilience, all of these things can help the incarcerated to grow.

If a change of heart is needed in order to transition back into the world of useful citizenship, so, too, are practical skills: a basic education, job skills, and a post-release plan. You can’t just boot people out the door when they’re released; they’ll need a well-structured plan, support systems, therapy, and job opportunities.

PREVENTING CRIME/PRISON ABOLITION

Prison activist Maya Schenwar writes, “We see prison as a solution to the problem of crime. Instead of preventing crime by allocating resources for healthcare, early childhood education, food, housing, and other basic needs, we’re sending people to prison.” While research shows that strong communities can promote public safety and reduce crime, high rates of incarceration are tearing poor communities apart.

Schenwar goes so far as to suggest that ultimately prisons themselves ought to be done away with, that society should explore other options for dealing with crime. It’s a bold proposal.

Prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba writes, “Our current historical moment demands a radical reimagining of how we address various harms. The levers of power are currently in the hands of an administration that is openly hostile to the most marginalized in our society…The US prison system is designed to crush people… Prison industrial complex abolition calls for the elimination of policing, imprisonment and surveillance. It rejects the expansion in breadth or scope or legitimization of all aspects of the complex.”

“Transformative justice is about trying to figure out how we respond to violence and harm in a way that doesn’t cause more violence and harm,” she goes on. “It’s asking us to respond in ways that don’t rely on the state or social services necessarily if people don’t want it…. Why do we have no other well-resource options? It pushes us to creatively consider how we can grow, build and try other avenues to reduce harm.”

How might Prout view the idea of prison abolition? While no official policy yet exists, it is self-evident that tossing inmates into a confounding environment means they often become ever more entangled in criminal behavior, creating a series of knots seemingly impossible to unsnarl. Some studies show that imprisonment actually increases crime. “Few people stop committing crimes because prison exists,” researcher Todd Clear writes. “Prisons are schools of crime, returning people to the community further criminalized.”

If this is the case, then society is shelling out for justice coming and going – taxes pay for the not insignificant costs of housing and feeding the convicted (a year in prison can cost more than a year at Harvard), and we pay again when new crimes are committed by those who have been traumatized and criminalized by the prison experience and are released back into society.

It’s also clear that there is no real justice when the poor and people of color are so disproportionately affected by the carceral system.

If our goal is not retribution, but restoration and wholeness, it only makes sense to put more money into objectives like drug treatment, education, housing, counseling and jobs, before outsiders become insiders. And to consider, for some, alternatives to incarceration, such as mental health courts, drug courts, community supervision, anger management programs, and halfway houses.

If we change how prisons operate, their guiding philosophies, and drastically reduce the numbers of people going to prison, offering alternatives to incarceration, the few prisons remaining may be able to do what they should do: rehabilitate behavior.

POLICY SUGGESTIONS

My opinion is that a Proutist policy on prison and criminal justice would be rooted in both restorative and transformative justice. This would include the opportunity for those convicted of crimes to meet with those impacted by their crimes, take responsibility for their actions, make amends, and see themselves as vital parts of the community… It would allow for the community itself to be mended, along with the lives of those who committed the crime.

Education would be a priority for those in prison, as well as the opportunity for self-development through the arts and creative expression, and mental health counseling.

There would be no scope for privately-run prisons, no opportunity for capitalists to make money off of the lives of those caught up in the justice system.

The needs of women would especially be attended to in the system, with zero tolerance for sexual harassment or discrimination.

Capital punishment would be done away with. There would be fairness without discrimination based on race, background, education level, socio-economic status, in application of the law. This would suggest greater prosecution of financial crimes, which these days are largely overlooked.

Sentencing reform would be key. As World Prison Brief notes, “The case for reform to increase the use of community-based sentences in the place of the current use of short prison sentences has been made on multiple grounds: proportionality, effectiveness at reducing reconvictions, morality, addressing underlying needs such as problematic drug use, and ensuring better outcomes for women caught up in criminal justice processes in particular. Other considerations include value-for-money, the additional demands the chaos and churn short stays of imprisonment place on prison staff time, and deteriorating conditions in the prison estate – the health risks of which were brought into sharper focus by the pandemic.”

In a Proutist world, drug laws and sentences would be reviewed to reflect the mostly non-violent nature of most offenses, and to redress the current racial bias in sentencing. Policing policies would be re-examined, zero tolerance policing done away with, and the police put to work doing what they are best at: not social work or mental health calls, but responding to crime. Alternative response systems for calls involving persons with disabilities and mental health issues could be implemented. Community-based policing, in which officers develop relationships with those they serve, would be encouraged. A Neohumanist outlook would be promoted among the police, with no tolerance for racism.

Mandatory sentencing laws, which have prevented judges from exercising discretion, would be done away with. The bail system would be reformed. Pretrial detention could be done away with for most defendants. Children and youth would not be prosecuted or sentenced as adults, but rather given opportunities for mentorship, treatment, education and a chance to develop their qualities.

Prosecutorial roles would be reined in. And post-release community corrections approaches need reform as well: doing away with pointless parole restrictions such as fines or inflexible scheduling, and ensuring that housing, transportation and jobs are available for released inmates. Common challenges for parolees, like missing appointments because of lack of transportation or housing, or being unable to pay fees, means thousands go back, pointlessly, to prison.

Sarkar recommended a common constitutional structure and a common penal code as part of an approach to global unity. A shared penal code across borders would contribute to stability on a regional level, and have an impact on immigration as well.

As noted, Sarkar also recommends the creation of more judges, of high moral character. This would ease the strain on the justice system and offer the opportunity for more mercy-based decisions.

There is also a great need for better training of prison workers. Prout would encourage the cultivation of relationships by prison workers with the imprisoned. As happens at Halden prison, an atmosphere of collegiality, respect, and independence will help in the reform process. Solitary confinement is considered by many experts to be a form of torture, and should be discontinued.

The design and atmosphere of rehabilitation centers would focus on compassionate reform. Such places would emphasize education, mental health treatment and the arts, and perhaps, spiritual practice. This is congruent with Prout’s vision of society, that every person, whether living in “normal” society or serving time in prison, should have the opportunity to grow and find meaning.

Of course, addressing the root causes of crime will be at the foundation of any Proutist policy. Creating a society free of poverty, with good education and jobs for all, with a focus on compassion, mental health, and a spiritual outlook, will go a long way toward redressing the ills of the current system.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, Michele, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (The New Press, 2012).

Benko, Jessica, “The Strange and Radical Humaneness of Norway’s Halden Prison”, New York Times Magazine (May 26, 2015).

Boyle, Greg, Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion (Free Press, 2011).

Bronson, Jennifer, and Berzofsky, Marcus, “Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates” (U.S. Department of Justice Special Report, 2011-2012).

Cohen, M. L. “Prison choirs: Studying a unique phenomenon”, Choral Journal (November, 2007).

Cohen, M. L., “Explorations of inmate and volunteer choral experiences in a prison-based choir”, Australian Journal of Music Education, 1 (2007)

Cohen, M. L., “Select music programs and restorative practices in prisons across the US and the UK”, Harmonizing the diversity that is community music activity: Proceedings from the International Society of Music Education (ISME) 2010 Seminar of the Commission for Community Music Activity, D. Coffman (Ed.), International Society for Music Education (2010).

Douglas, Andy, Redemption Songs: A Year in the Life of a Community Prison Choir (Innerworld Publications, 2018).

Dreisinger, Baz, Incarceration Nations (Other Press, 2017).

Edge, Laura, Locked Up: A History of the US Prison System (Twenty-first Century Books, 2009).

Friedman, Lawrence, Crime and Punishment in American History (Basic Books, 1994).

Frisch, Tracy, “Criminal Injustice: Maya Schenwar on the failure of mass incarceration”, The Sun (June 2015).

Gopnik, Adam, “The Caging of America”, The New Yorker (Jan 30, 2012).

Gunn, John, “Criminal behaviour and mental disorders”, British Journal of Psychiatry 130 (1977).

Hinton, Elizabeth, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America(Harvard University Press, 2017).

Kabe, Mariame, We Do This Til We Free Us

Karpowitz, Daniel, and Kenner, Max, “Education as Crime Prevention: The Case for Reinstating Pell Grant Eligibility for the Incarcerated” (Bard Prison Initiative, 1995).

Kittle, Bruce, “More to restorative justice than meets the eye”, Iowa City Press-Citizen (April 29, 2016).

Lee, Don, “Finding Freedom Through Song”, The Voice (Spring, 2014).

Logan, James Samuel, Good Punishment? Christian Moral Practice and US Imprisonment (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008).

Maruschak, Laura M., BJS Statistician, Berzofsky, Marcus, Dr., and Jennifer Unangst, RTI International, “Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates”, (U.S. Department of Justice 2011–12).

Perkinson, Robert, Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire (Picador, 2010).

Pfaff, John, “How we misunderstand Mass Incarceration”, The New Yorker (April 10, 2017).

Roeder, Oliver, Eisen, Lauren-Brooke, and Bowling, Julia, “What Caused the Crime Decline?” NYU Brennan Center Brennan Center for Justice (2015).

Sarkar, P. R., A Few Problems Solved Part 6 , (Ananda Marga Pracaraka Samgha, 1988).

Schenwar, Maya, Locked Down, Locked Out: Why Prison Doesn’t Work and How We Can Do Better (Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Oakland, 2014).

Surowiecki, James, “A Trump Bonanza for Private Prisons”, The New Yorker (December 5, 2016).

Williams, Rachel Marie-Crane, (Ed.), Teaching the Arts behind Bars (Northeastern Press, 2003).

ONLINE SOURCES AND RESOURCES

Iowa Department of Corrections FY2012 Annual Report

https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/SD/16260.pdf![]() prisonpolicy.org

prisonpolicy.org

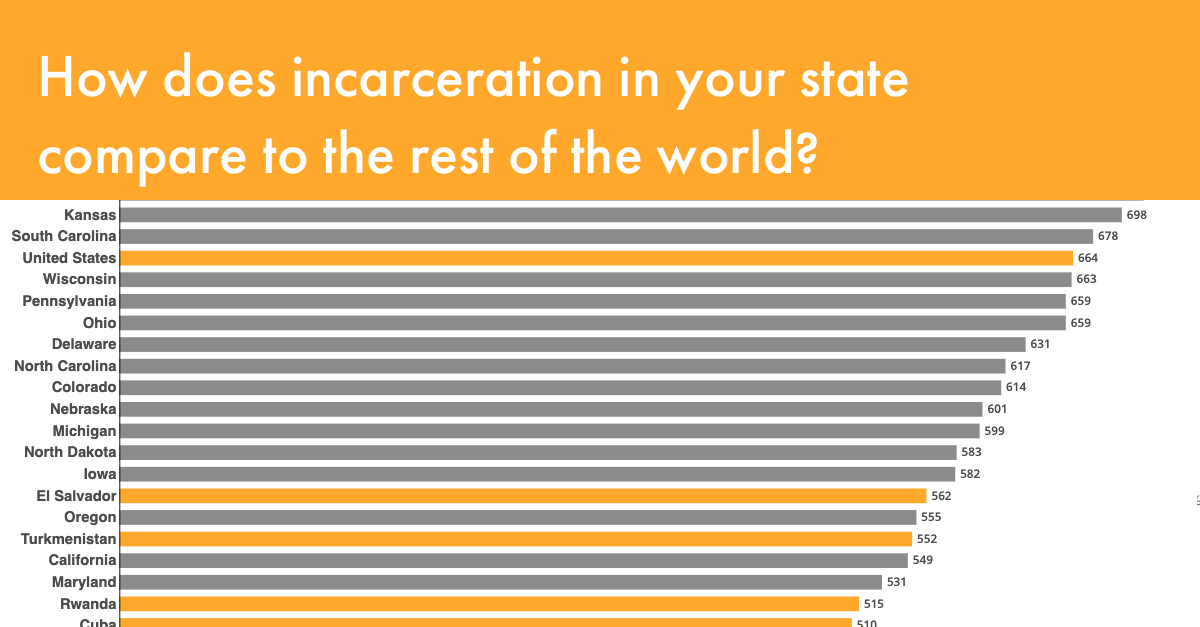

States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021

Criminal justice policy in every region of the United States is out of step with the rest of the world.

https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/abstractdb/AbstractDBDetails.aspx?id=252565FRONTLINE

Todd Clear: Why America’s Mass Incarceration Experiment Failed

It devastates communities and doesn’t stop crime, the Rutgers University provost explains.

Recidivism

Recidivism is measured by criminal acts that resulted in rearrest, reconviction or return to prison with or without a new sentence during a three-year period following the person’s release. Recidivism research is embedded throughout NIJ-sponsored…

http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/browse-by-state/iowa

US: Disastrous Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use | Human Rights Watch.

Arts-In-Corrections Program Returns to California Prisons

The California’s Arts-in-Corrections program administers platforms for bringing visual, performing, literary, and media arts to state prison inmates.

Solitary confinement facts | American Friends Service Committee.

Human Rights Watch – 27 Jan 12

Old Behind Bars

Summary Life in prison can challenge anyone, but it can be particularly hard for people whose bodies and minds are being whittled away by age.

http://Prisonstudies.org (world prison brief)

Sentencing and Prison Practices in Germany and the Netherlands

The U.S. prison population has increased 700 percent in the last 40 years, and state corrections expenditures reached $53.5 billion in 2012. Despite this massive investment in incarceration, the national recidivism rate remains at a stubborn 40…prisonstudies.org

world_prison_population_list_11th_edition_0.pdf

586.26 KB

Some of us know that the very Prout’s founder, P.R.Sarkar refered to some people as “born criminals”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Personality_disorder

It is true. He did mention that some people are born with mental disorders which make them prone to commit crimes. They should be treated for their condition and welcomed as fully functioning members of society once they are cured. If a cure is not possible, then they should be provided conditions to live as normal a life as possible within the limitations needed to keep everyone else safe.